- Home

- Perspective

- One Point Perspective Drawing

One-Point Perspective Drawing Made Simple

If you have ever looked down a long, straight road and noticed how the edges seem to squeeze together in the distance, you have already seen one-point perspective in action. The good news? Drawing it is just as intuitive as seeing it.

One-point perspective is the friendliest place to start your perspective journey. It is the simplest form of linear perspective, and once you understand it, you will have the foundation for everything else.

I use one-point perspective whenever I am sketching scenes where I am looking straight down something - a country path winding into the distance, a hallway in an old building, or a simple room interior. It is perfect for these subjects because you only need one vanishing point (hence the name!).

By the end of this page, you will have drawn three different scenes using this technique. No complex maths, no intimidating diagrams - just practical exercises you can do right now with a pencil and some scrap paper.

If you have not already, you might find it helpful to read my overview of basic perspective concepts first. But if you are eager to jump straight in, that is fine too - I will explain everything you need as we go.

What is One-Point Perspective?

One-point perspective is the technique we use when we are looking straight at a scene, with one surface facing us directly.

Imagine standing in a doorway and looking into a room. The back wall faces you squarely - it is flat and parallel to your eyes. The floor stretches away from you, the ceiling goes overhead, and the side walls angle off to either side. All those surfaces that are moving away from you appear to converge towards a single point in the distance.

That single point is your vanishing point. And because there is only one of them in this type of perspective, we call it one-point perspective.

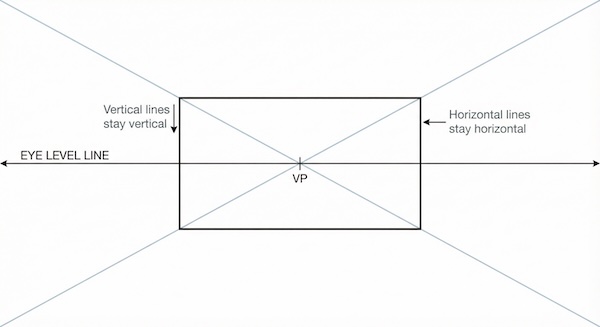

Here is what makes it straightforward: in one-point perspective, only the lines showing depth (the ones going away from you) angle towards the vanishing point. All the lines showing height stay perfectly vertical. All the lines showing width stay perfectly horizontal. That's it.

When should you use

one-point perspective?

It is ideal for:

- a straight road, path, or railway track disappearing into the distance;

- viewing the inside of a room from the doorway;

- a corridor or hallway stretching away from you;

- a row of buildings viewed straight-on;

- and simple still life objects like books lying flat on a table.

The Two Things You Need to Know

Before we start drawing, let us make sure we are clear on the two essential ingredients. Get these right, and everything else follows naturally.

Your Eye Level Line

The eye level line (sometimes called the horizon line) is simply an imaginary horizontal line that sits at your eye height as you look at a scene.

If you are standing and looking across a flat landscape, your eye level line is where the land meets the sky. If you are sitting down, it is lower. If you are looking down from a balcony, it is higher up in the scene.

Why does it matter? Because everything in your drawing relates to this line. Objects that are below your eye level - you will see their tops. Objects above your eye level - you will see their undersides.

I always draw my eye level line first, very lightly, before anything else. It is my anchor for the whole drawing.

The Vanishing Point (VP)

The vanishing point is the spot where all the lines showing depth appear to meet and vanish into the distance.

Think about those railway tracks. You know they are parallel in reality, running alongside each other. But when you look down them into the distance, they appear to get closer and closer together until they seem to touch at a single tiny point. That is your vanishing point.

In one-point perspective, your vanishing point always sits on your eye level line. Usually, it is somewhere near the centre of your scene - though you can move it left or right to create different viewpoints.

Practical tip: I mark my vanishing point with a small cross rather than just a dot. It is much easier to aim your lines accurately at a cross.

Right, that is enough theory. Let us draw something!

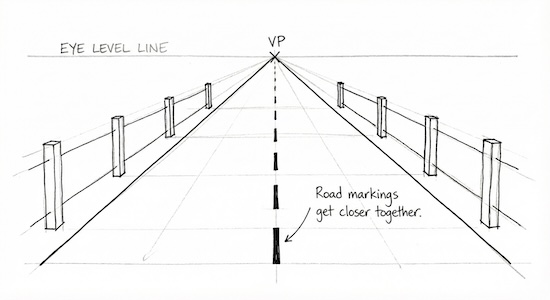

Exercise 1: Draw a Simple Road

This is the classic one-point perspective exercise, and for good reason. It is simple, it is satisfying, and it really drives home how converging lines create that sense of depth.

You will need: A piece of scrap paper and a pencil. A ruler helps but is not essential.

Time: About 5-10 minutes

Step 1: Draw your eye level line

Lightly draw a horizontal line about one-third down from the top of your paper. This represents the horizon - where the road will disappear into the distance.

Step 2: Place your vanishing

point.

Put a small cross roughly in the centre of that eye level line. Label it VP if that helps you remember what it is.

Step 3: Draw the road edges

From the bottom left corner of your paper (or just inside it), draw a straight line up towards your VP. Now do the same from the bottom right corner. These two lines are the edges of your road, stretching away into the distance.

Notice how the road appears wider at the bottom (close to you) and narrower at the top (far away)? That is perspective working.

Step 4: Add the centre line

Draw a line from the centre-bottom of your paper up to the VP. This is the road's centre marking.

Step 5: Make the markings

shrink

Here is where it gets fun. Draw short vertical lines along your centre line to represent the road markings. But here is the key: make them shorter and closer together as they get nearer the VP.

The lines at the bottom of your road might be 2cm apart. Halfway up, maybe 1cm. Near the VP, they are almost touching. This creates the powerful illusion that the markings are evenly spaced but receding into the distance.

Step 6 (Optional): Add some scenery

Draw fence posts or telegraph poles along the road edges. Start with taller ones at the bottom of your drawing, and make them progressively shorter as they approach the VP. Space them closer together too, just like your road markings.

And there you have it - a road disappearing convincingly into the distance!

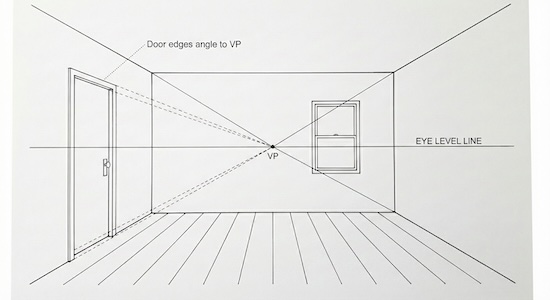

Exercise 2: Draw a Room Interior

This is probably the most useful one-point perspective exercise you will ever do. Once you can draw a room, you can draw furniture, shelves, windows, doorways - essentially any interior scene.

You will need: Paper, pencil, and a ruler is quite helpful here.

Time: About 10-15 minutes

Step 1: Draw the back wall.

Draw a rectangle in the centre of your paper. This is the far wall of your room - the wall you are looking directly at. Leave plenty of space around it on all sides.

The size of this rectangle determines how deep your room will feel. A smaller rectangle = a deeper room. A larger rectangle = a shallower room.

Step 2: Mark your eye level and VP

Draw a light horizontal line through the middle of your rectangle. This is your eye level. Place your VP (as a small cross) in the centre of the back wall.

Step 3: Connect the corners

From each of the four corners of your rectangle, draw a line extending outwards towards the corners of your paper. These create your floor, ceiling, and side walls.

Look at that - you have already got a recognisable room!

Step 4: Add a window on the back wall

Draw a smaller rectangle on your back wall. Because this window is on a surface that is facing you directly (parallel to your face), it stays a simple rectangle - no perspective distortion needed.

Step 5: Add a door on the side wall

Now here is where it gets interesting. Draw a door on one of the side walls (let's say the left one).

The vertical edges of the door stay straight up and down - parallel to the edge of your paper.

But the top and bottom edges of the door? They angle towards your VP. Draw a light line from the top of the door frame towards the VP, and another from the bottom towards the VP. This makes the door look like it is properly sitting on that receding wall.

Step 6: Add floorboards

For wooden floorboards running away from you, draw lines from the bottom edge of your back wall towards the VP. Space them evenly along the back wall, and watch how they spread out as they come towards you.

Want floor tiles instead? Add horizontal lines across your floor, spacing them closer together as they approach the back wall.

Common mistake to avoid: Do not put your VP outside the back wall rectangle. If the VP is above the back wall, your room will look like you are staring up at the ceiling. If it is below, you will be staring at the floor. Keep it within the wall for a natural, straight-ahead view.

Exercise 3: Draw a Corridor with Doorways

This exercise combines everything you have learned. It is essentially a longer, narrower room with multiple doorways - perfect for understanding how repeated elements shrink with distance.

You will need: Paper, pencil, ruler helpful

Time: About 15-20 minutes

Step 1: Set up your corridor

Draw a small rectangle for the far end of the corridor (smaller than your room's back wall - this corridor is longer). Mark your eye level and VP in the centre as before. Connect the corners to create the floor, ceiling, and walls.

Step 2: Add the first

doorway on the left.

Place it fairly close to the front of your corridor (near the bottom of your drawing). Remember: vertical edges stay vertical, but the top and bottom of the doorway angle towards the VP.

Make this first doorway fairly large - it is the closest to us.

Step 3: Add a second doorway further back

This one should be: shorter (it is further away, so it appears smaller), narrower (the width shrinks with distance too), and positioned with its base higher up on the wall (closer to the eye level line).

Step 4: Add a third doorway even further back

Smaller again. You will notice the doorways appear to get closer together as well as smaller. This is correct! In perspective, equal distances appear compressed as they recede.

Step 5: Repeat on the right

side.

Add corresponding doorways on the right wall. Try to line them up with the left side - the tops and bottoms of matching doors should align horizontally (or very nearly).

Step 6: Add ceiling lights.

Draw rectangles on the ceiling representing light panels or fixtures. These should get smaller and closer together as they approach the VP - exactly like your road markings in Exercise 1.

Observation prompt

Next time you are in a real hallway or corridor, pause and look. Notice how the doors, lights, and floor tiles all seem to converge towards a point in the distance. You have just drawn exactly that!

Using One-Point Perspective in Your Coloured Pencil Work

So how does all this translate to your actual art practice?

When I am starting a coloured pencil piece that involves perspective, I always begin with a light graphite sketch using these principles. The eye level line, the vanishing point, and a few guide lines are all I need to establish a solid foundation.

These construction lines do not need to be perfect or elaborate. They are just guides that will be completely covered by your coloured pencil layers. Once the main shapes are established correctly, I erase most of the guide lines before picking up my coloured pencils.

One-point perspective works

beautifully for:

- A garden path leading to a focal point (perhaps a bench, a gate, or a splash of flowers).

- A country lane winding between hedgerows.

- A simple street scene viewed from one end.

- A bookshelf viewed straight-on (the shelves recede in one-point perspective).

- An interior scene like a cosy kitchen or studio.

- A railway line or bridge stretching into a landscape.

The beautiful thing about getting your perspective right at the sketch stage is that it sets up your whole piece for success. When the underlying structure is sound, your layered coloured pencil work will look convincing and solid.

Quick Reference Checklist

Before you move on, use this checklist to make sure you have got the essentials:

- Eye level line drawn first, lightly, as your anchor?

- Single vanishing point placed on the eye level line?

- All lines showing depth converge at the VP?

- Vertical lines stay truly vertical?

- Horizontal lines facing you stay truly horizontal?

- Objects get smaller AND closer together with distance?

What's Next?

You have now got a solid grasp of one-point perspective. The three exercises on this page cover the most common applications: open scenes like roads, enclosed spaces like rooms, and repeated elements like corridors.

My advice? Do not just do each exercise once and move on. Grab some scrap paper and draw a few more roads, a couple more rooms. Try changing the position of your VP - what happens when it is far to the left? To the right? This kind of playful practice is how the concepts really sink in.

When you are feeling confident with one-point perspective, you are ready for the next step: two-point perspective. This is what you will use when you are looking at the corner of something rather than straight at it - essential for drawing buildings, furniture, boxes, and a huge range of other subjects.

Continue to Two-Point Perspective → Draw Buildings and Objects That Look Real

Or if you would like to review the foundational concepts: Back to Perspective Drawing Overview

Now go draw some roads! Seriously - right now, while it is fresh. Even a quick 5-minute sketch will help cement everything you have learned.