- Home

- Perspective

- Two Point Perspective Drawing

Two point perspective drawing

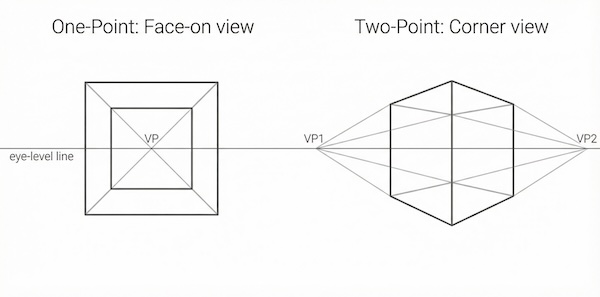

If one-point perspective is about looking straight down a road, two-point perspective is about standing at a street corner and looking at the buildings around you.

It is the perspective type I use most often in my own work, and once you have got it, you will be able to draw buildings, furniture, boxes, and countless other subjects with real confidence.

The key difference? In two-point perspective, you are looking at the corner of something rather than facing it head-on. You see two sides of the object receding away from you.

Don't worry if that sounds complicated. By the end of this page, you will have drawn boxes, a building, and even a table and chair. Ready? Let’s go.

If you have not yet worked through one-point perspective, I would recommend starting there first. The concepts build on each other, and you will find two-point much easier if you have already practiced with one vanishing point.

What is Two-Point Perspective?

Two-point perspective is the technique we use when we are looking at an object from an angle — specifically, when we can see two walls or faces of it: one going off to your left, and one going off to your right. Each direction has its own vanishing point.

The left side’s edges all angle towards a point on the left (we will call it VP1). The right side’s edges all angle towards a point on the right (VP2).

Here is what stays the same: Just like in one-point perspective, vertical lines stay vertical. The corner of the building, the edges of windows, the sides of doors - they all go straight up and down, parallel to the edges of your paper.

Here is what is different: Instead of horizontal lines staying horizontal, they now angle towards one of the two VPs. Lines on the left-facing surface go to VP1. Lines on the right-facing surface go to VP2.

When should you use

two-point perspective?

Furniture (tables, chairs, cabinets, beds), boxes and packages, books on a shelf turned slightly, vehicles like cars and vans, and other rectangular objects that are not facing you square-on.

The Critical Setup: Placing Your Vanishing Points

Here is where most beginners go wrong with two-point perspective, so please pay attention to this section. It will save you a lot of frustration.

Your Eye Level Line

Start by drawing your eye level line - a light horizontal line representing your eye height. Everything in your drawing relates to this line.

If your eye level is low (line near the bottom of the paper), you are looking up at objects - you will see the undersides of things above you. If your eye level is high (line near the top), you are looking down - you will see the tops of things below you.

Placing Your Two Vanishing Points

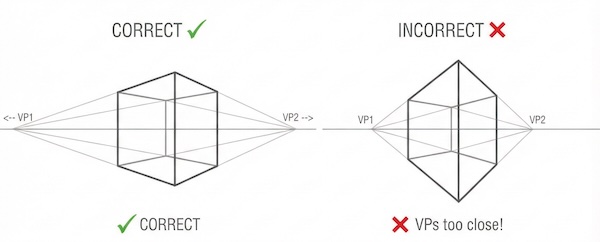

This is crucial: Your two vanishing points need to be far apart. Much further apart than you might think.

If you place VP1 and VP2 too close together, your objects will look distorted - stretched, squashed, or bent in unnatural ways. It is a bit like looking through a fish-eye lens. Sometimes artists use this deliberately for dramatic effect, but for realistic drawings, you want to avoid it.

My practical advice: Place your VPs near or even beyond the edges of your paper. I often stick small pieces of tape or sticky notes on my desk, either side of my drawing, to mark where my VPs are. It looks a bit odd, but it works brilliantly.

Both VP1 and VP2 must sit on the same eye level line. VP1 goes on the left, VP2 on the right.

The Foundation: Drawing a Two-Point Box

Before we draw buildings or furniture, we need to master the box. Every building is essentially a boxand so are most everyday things. Master this, and you can draw almost anything.

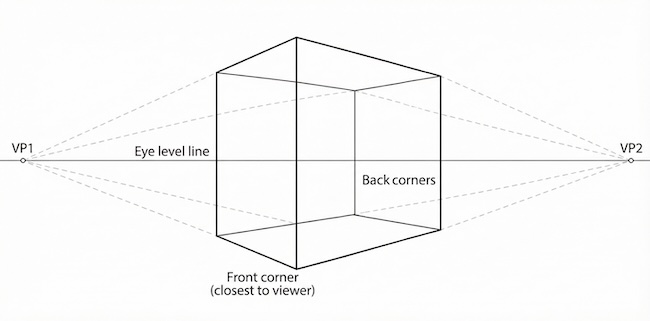

Quick step-by-step:

- Use the eye level line and VPs you set up above (VP1 on the left, VP2 on the right, far apart).

- Draw a single vertical line. This is the front corner of your box - the edge closest to you. Make it as tall as you want your box to be.

- From the top of that vertical line, draw one line angling towards VP1 and another angling towards VP2.

- From the bottom of that vertical line, draw one line towards VP1 and another towards VP2.

- Draw two more vertical lines to create the back corners - one on the left side (between your VP1 guide lines) and one on the right side (between your VP2 guide lines).

- Complete the top of the box by connecting the back corners. The left back corner connects to VP2; the right back corner connects to VP1. These lines should meet at the back edge of the box.

- And there you have it - a box in two-point perspective!

Exercise 1: Draw a Row of Boxes

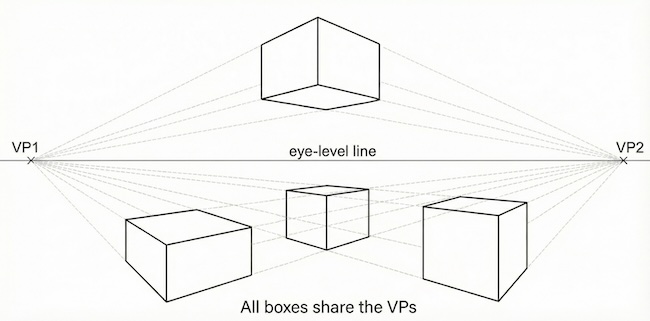

Now let us practice by drawing multiple boxes in the same scene. This reinforces a crucial point: every object in your scene shares the same vanishing points.

You will need: Paper (A4 or larger helps), pencil, ruler, and optionally sticky notes to mark your VPs.

Time: About 10–15 minutes

- Use the eye level line and VP1/VP2 setup from the section above.

- Draw your first box below the eye level line (so you will see its top), using the box method you just learned.

- Draw a second box to the left of the first. Notice how the angles of the lines change because the box is in a different position — that is correct.

- Draw a third box to the right.

- Vary the sizes. Make one box tall and narrow, another short and wide. They should still look like they belong in the same space.

- Draw a box above the eye level line. You will see its bottom instead of its top.

What you have learned: All objects in a single scene share the same vanishing points. The position of an object relative to the eye level determines which surfaces you see.

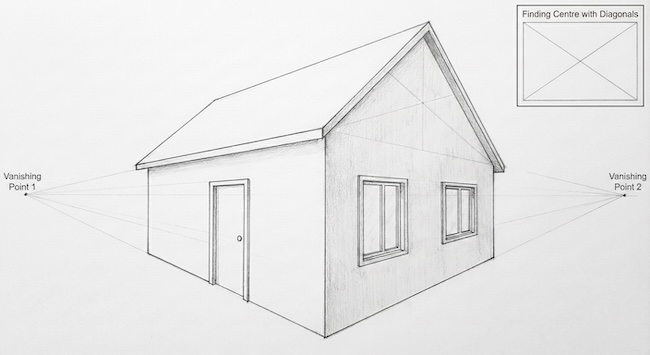

Exercise 2: Draw a Simple Building

This is where two-point perspective really shines.

Being able to sketch a convincing building quickly is incredibly useful — whether you are planning a landscape painting, capturing a scene from your travels, or adding architectural elements to a coloured pencil piece.

You will need: Paper, pencil, ruler (strongly recommended).

Time: About 15–20 minutes

- Use the same eye level line and VP1/VP2 setup from the section above (far apart, on the same line).

- Draw a vertical line for the corner of the building nearest to you. Keep it below the eye level line so you will see the roof.

- From the top of that corner line, draw one line towards VP1 and one towards VP2. From the bottom, draw lines towards both VPs to set where the walls meet the ground.

- Decide how wide each wall should be. Draw vertical lines to mark where each wall ends (the back corners of the building).

- Find the centre of the front wall (the gable end): draw light diagonals from corner to corner. Where they cross is the centre. Draw a vertical line up from that point — this marks where the roof peak will sit.

- Draw the roof. Connect the roof peak to the two top corners of the front wall to create the triangular gable. Then extend the roof ridge back towards the correct vanishing point and connect it down to the back corner to complete the slope.

- Add a door on one wall. Keep the door sides vertical, and angle the top and bottom edges towards the vanishing point for that wall.

- Add windows using the same rule as the door.

Common mistakes to avoid:

- Door and window frames that do not angle to the correct vanishing point (they will look stuck on rather than receding).

- Roof peak not centred (makes the building look lopsided).

- Mixing up which vanishing point belongs to which wall (always double-check before committing darker lines).

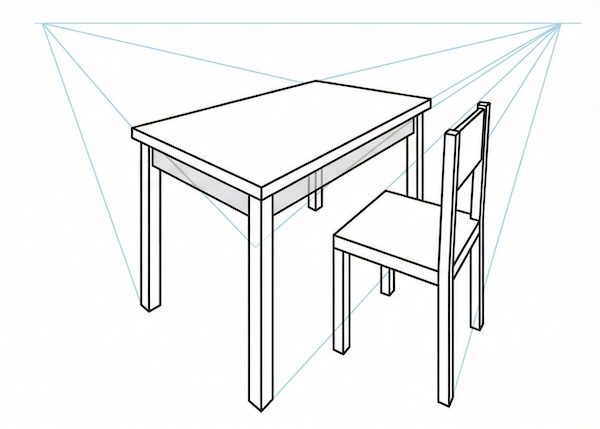

Exercise 3: Draw a Table and Chair

Furniture is the ultimate test of two-point perspective because it combines multiple box-like forms. If you can draw a table and chair correctly, you can handle almost any interior scene.

You will need: Paper, pencil, ruler (helpful).

Time: About 20–25 minutes

Drawing the Table

- Use the same eye level line and VP1/VP2 setup from earlier (far apart, on the same line).

- Draw the tabletop as a flat, wide box (a thick slab of wood). Start with the front corner edge, connect to both VPs, and complete the top surface.

- Add thickness: drop short vertical lines down from the front corner and the two visible back corners, then connect those new points back to the VPs to form the underside.

- Mark the leg positions. Table legs sit slightly inset from the corners, not right on the edges. Lightly map an inset rectangle on the underside to show where the legs attach.

- Draw four legs straight down from those points. Keep the legs truly vertical (they can taper slightly, but don’t let them slant).

- (optional): Add crossbars between legs near the bottom. Keep the bars’ edges aiming to the correct vanishing point for their direction.

Drawing the Chair

- Draw the seat first as a smaller, thinner box.

- Add four legs, slightly inset from the seat corners. Keep them vertical.

- Add the chair back: a flat rectangular panel rising from the back edge of the seat. Its top and bottom edges should angle to the correct vanishing point for that direction.

- (optional): Add back slats/spindles as vertical lines between the top and bottom of the chair back.

Arranging the Scene

Place the chair slightly off to one side of the table, as if someone pushed it back after a meal. Keep the chair seat clearly lower than the tabletop, and ensure both pieces sit in the same perspective setup.

Troubleshooting

- Table looks wobbly? Your vanishing points may be too close together, or your legs aren’t truly vertical.

- Chair looks too big? Reduce it relative to the table (especially seat height and width).

- Legs look splayed? Re-check that you drew them straight down, not angled.

Once you can keep a table and chair consistent in one setup, you’ve learned the real skill: thinking in simple 3D forms in space—and that applies to far more than architecture.

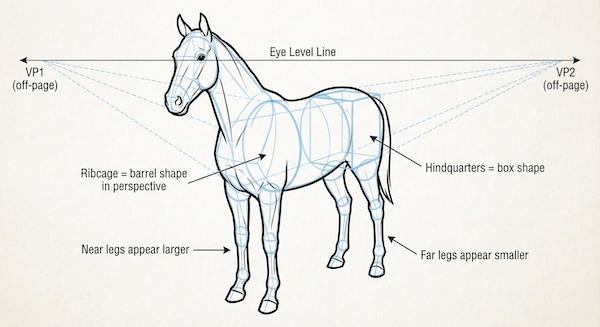

Perspective is Not Just for Buildings

When you look at a horse from an angle, you are essentially looking at a series of connected box and cylinder shapes: the ribcage as a barrel, the hindquarters as a rounded box, and the head as a wedge.

When I sketch a horse (or any animal) for a coloured pencil piece, I start by lightly blocking in those basic 3D forms first. Once the construction shapes feel solid, adding the organic curves and details on top becomes much easier.

Look at the diagram below. Notice how the far legs appear shorter and narrower than the near legs? That is perspective doing its job. The same compression happens through the body too.

So if an animal feels “off” in your drawing, try building it as simple boxes and cylinders first, check the perspective, and then refine the forms.

Using Two-Point Perspective in Your Coloured Pencil Work

When a piece includes buildings, furniture, vehicles, or any other box-like forms, start with a light graphite construction sketch: establish your eye level line, place VP1 and VP2, and use a few guide lines to lock in the big shapes.

Keep these construction lines simple. They are just temporary guides that will be covered by coloured pencil layers. Once the main shapes feel solid, lightly erase most guides before you begin colouring.

A simple habit that helps: before you commit to darker lines or colour, do a quick check that each set of edges is aiming to the correct vanishing point.

Quick Reference Checklist

- Eye level line in place

- VP1 and VP2 placed far apart on the eye level line

- Left-facing edges aim to VP1, right-facing edges aim to VP2

- Vertical edges are truly vertical

- Everything in the scene uses the same VP1/VP2

What's Next?

Fill a page with boxes: some above eye level, some below, in different sizes. Then draw a simple building, and finally sketch an animal using light box/cylinder construction first.

If you have not already worked through one-point perspective: One-Point Perspective Made Simple

For an overview of both types: Perspective Drawing Overview